Nigeria, a nation lost to the gods

Bénédicte Kurzen

Pulitzer Center

Counting bodies in Nigeria is an endless task, day after day; and there are endless announcements of bomb attacks: on churches and police stations, in Maiduguri, Kano, Damaturu and Gombe. “Bombs are our daily bread.” But as the situation in Maiduguri degenerates into a state of open guerilla warfare, there are still a very few profitable businesses in the region, such as Mr. Mari’s hotel which houses Nigerian army officers.

It is not easy to convey the idea of the chaos prevailing in the northern part of the Federation of Nigeria. Nothing is easy in Nigeria. Religious tension flared up just as the military regime came to an end, in 1999. Once the country was freed from dictatorial rule, it split in two once again. Nigeria is an extraordinarily diverse society with more than 200 ethnic groups, and was amalgamated as one country under British colonial rule when Lord Lugard was Governor in 1914. One century later, the amalgamation appears both obsolete and insoluble.

This report began with the presidential election which triggered political tension, made immediately worse by religious conflict. When the Muslim opposition candidate Muhammadu Buhari was defeated by Goodluck Jonathan, the North lost any real political influence and is now effectively sidelined for the next three years. This proved too much for the people to bear; their sense of frustration at being used and exploited by corrupt politicians could no longer be contained, and within a few days 800 people had died. In the mainly Christian South, which has the oil reserves, the economy was thriving - it is one of the most dynamic economies in Africa. In the North, 75% of the population live on less than 150 euros a year. In the North, the economy is declining and illiteracy has reached record levels.

Preview

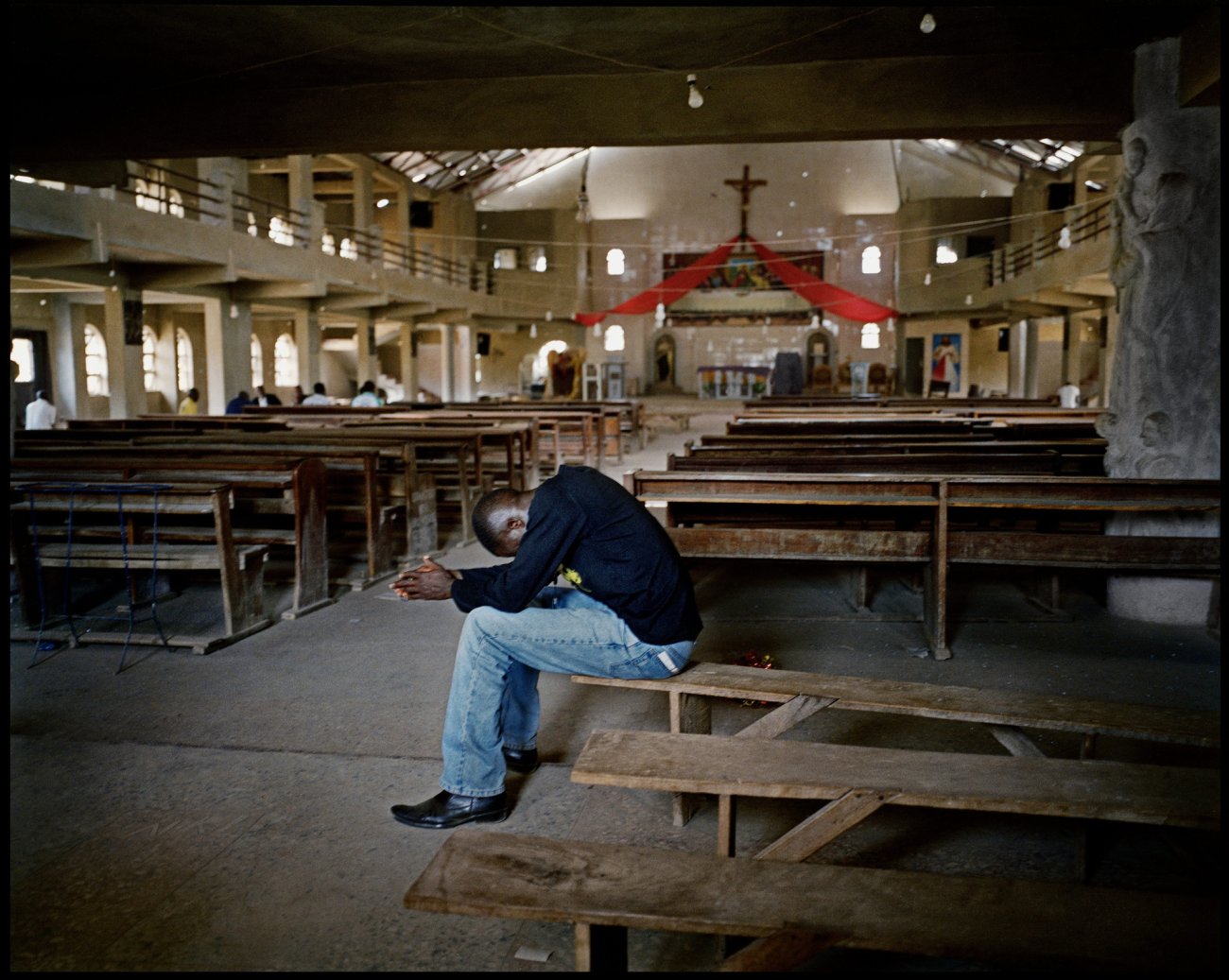

This is the melting pot which has provided the recruits for the insurrection raging in the northern half of the country for the past two years. Attacks carried out by Boko Haram (the Hausa name for Jama’atu Ahlis Sunna Lidda’awati Wal-Jihad), which has killed more than a thousand people since 2009, have brought terror to the people. Boko Haram is a radical Islamist jihadist group, originally from Borno State; it advocates strict application of Sharia law, abolition of the secular system, and total rejection of Western values, and has been conducting a relentless campaign against Christians, the army and police. In January 2012, a state of emergency was declared in a number of Local Government Areas, and power was handed over to the armed forces, forces renowned for their brutality and lack of discipline; there have been eye-witness reports of summary executions. Local communities are trapped between the factions and while huge sums have been allocated for security (a record 20% of the federal budget), the Boko Haram sect has managed to remain beyond the reach of the authorities.

In central Nigeria, Christians and Muslims meet; this is the Middle Belt, including Jos, and is the epicenter of long-standing religious and ethnic violence. Local politicians, such as Plateau State Governor Jonah Jang, have spread religion and also mistrust, verging on hatred. The locals say that they are on one of the front lines in a war of religion which broke out on 9/11. Global issues combine and compound local issues and each successive crisis only increases divisions between communities, and that applies to all communities: Berom, Hausa, Fulani, Ngas, native and non-native. A local motto - Land of Peace and Tourism - is now a distant mirage, a long-faded memory

How do these communities whose beliefs are diametrically opposed live together as part of a single nation where, day after day, anger and frustration grow greater? What is left as the social contract collapses, undermined by those in power who prevail through extreme corruption and injustice?

This report, covering more than one year, endeavored to explore the sectarian violence and observe, if not the reasons at least the symptoms, as seen in the harsh, murky light of the North. It is impossible to uncover the underground sources feeding the violence; they are organic, secret groups, with as many of them as there are identities in Nigeria.

Bénédicte Kurzen June 18, 2012, Jos, Plateau State, Nigeria.

I wish to express my sincere gratitude to the Pulitzer Center for the crucial financial support provided and also to Joe Bavier for his support.