Sufism

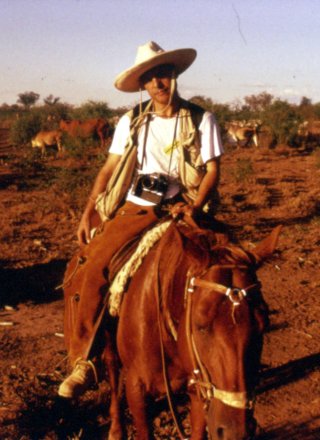

Bruno Hadjih

My first encounter with the Sufis was in Algeria. It took place in the desert. Through them I discovered another view of Islam. A free and tolerant Islam. I heard names I had never heard before: names such as Mansour El Haladj, Ibn Arabi and others. Names which became familiar and which I understood much later.

Preview

Four years after this trip to Algeria, I found myself covering a story in the Penjab, in Pakistan, an orthodox Islamic country and, if the news is to be believed, a difficult country. And there, once again, I met the Sufis. After a long stay with them I came to know their particular ways. These ways they called tarika. The schools of thought they called salsila. Dhikr, damask and music. Every passing day I am astonished by the extent of the goodwill the Sufis have towards me. Whole nights spent listening to kawali, the songs of the Sufis. From time immemorial fraternities have been formed through poetry, as poetry alone can express the mysticism of its beauty. Verses expressing the intoxication of love have traeled across the boundaries of the Orient. When it seems that in other places violence is ubiquitous and all hope of freedom is futile, the Sufis' response is this poem by Mir Dard: Reflect, O friend, on the unity of it all. See how the petals come together to form a rose. In the garden of the world we are at once the rose and the thorn We are friend and we are enemy'

Their freedom of spirit leads them sometimes to draw blame on themselves. Mansour El Haladj, the most famous of them, shouted the words 'I am truth' at those who tortured him for alleged heresy. In other words 'I am God'.

What of the Kalandari, those free-thinkers of Islam for whom the way to God can be achieved through any means. It comes through opium, hashish, asceticism and song. They grow their hair long, and their beards, they have follow different paths to allow their spirit to focus essentially on God. They take possession of cemeteries, sitting on the tombs, seeking to capture the sanctifying power of their master. They give thanks to him through songs or recite ghazals (poems) until daybreak. Their thought heralded the Malamati movement, that is to say the 'blameworthy'. Their words are still rejected today by the Orthodox. They are heretics. Their words express a freedom of thought which is also visible in their actions.

Abu Yazid El Bistani, one of the first Kalandari Sufis of the 9th century A.D., was once asked about asceticism. He replied: "It is worthless. My asceticism lasted three days.

On the first day, I renounced this world. On the second, I renounced the Hereafter. On the third, everything which is not God. Then I heard the call: "What do you want?" "Not to want anything", I replied, "for I am the one who is wanted and you are the one who wants" ".

Much later, I met with other groups of Sufis, the Naqshbandi in Uzbekistan, the Qadiri in India and Egypt, the Aïssaoua in Morocco, the Mawlana (whirling dervishes) in Turkey. All have that beauty in their eyes, the beauty of their souls, the beauty of their hearts.

I kept company with them for over a decade.

Several times, I felt discouraged. I wondered about the continuity of it all. And often I found answers in other places. In Multan, I felt reassured. In Ajmer, the validity of my approach was confirmed. In Boukhara, I felt carried away. My relationship with these groups is based on trust. Several stays were necessary to grasp the quintessence of these places.

This exhibition has been produced with the support of Geo.