Tribute to Fifi

Françoise Demulder

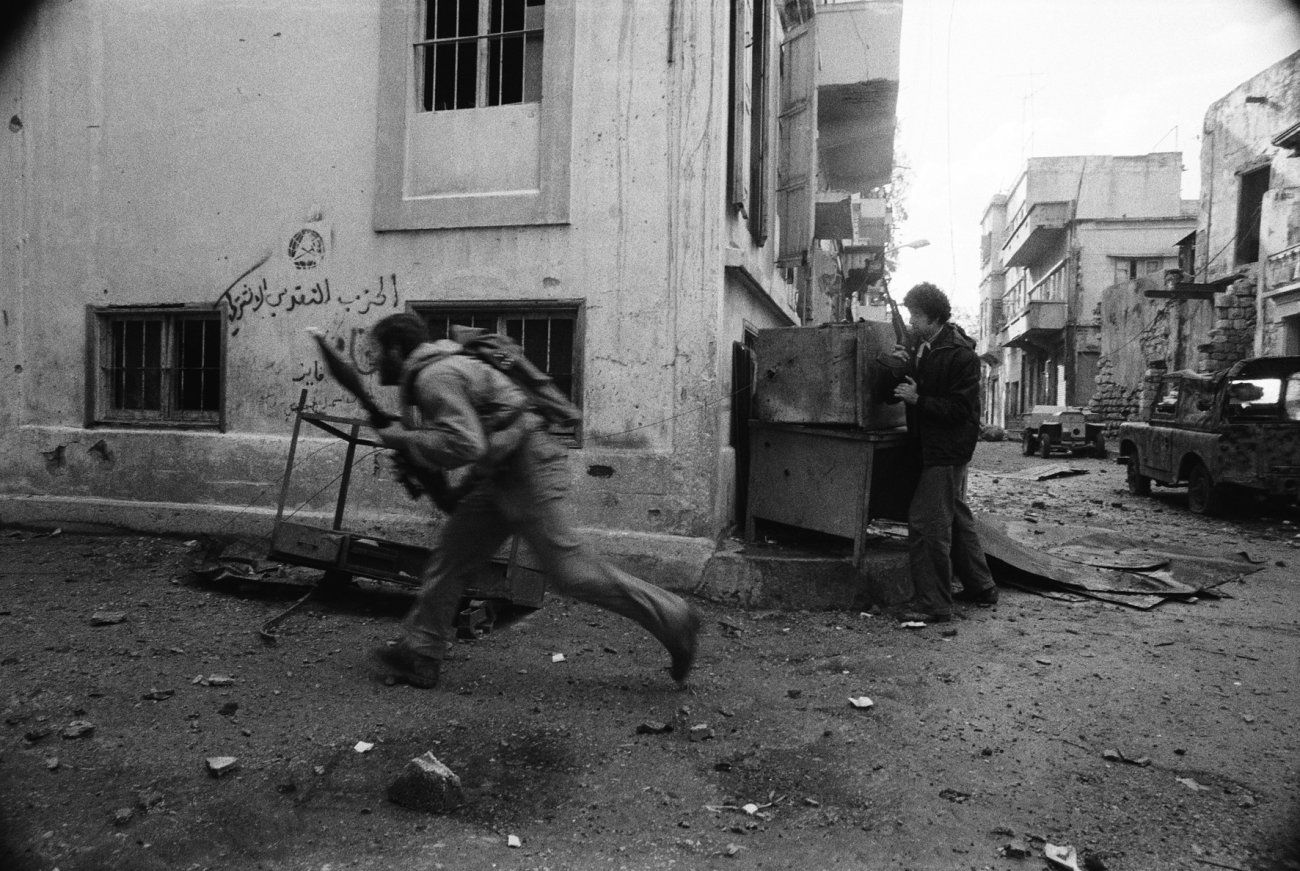

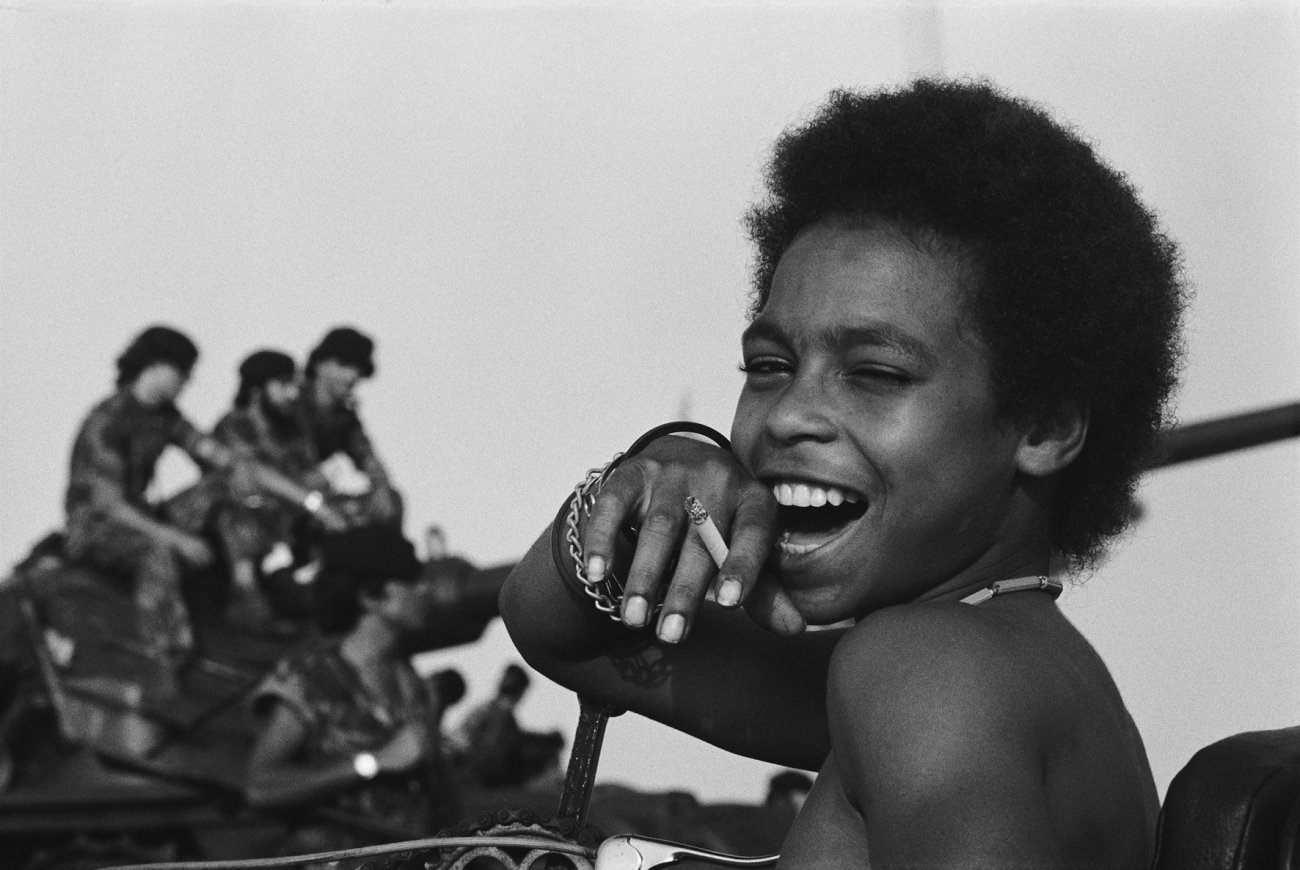

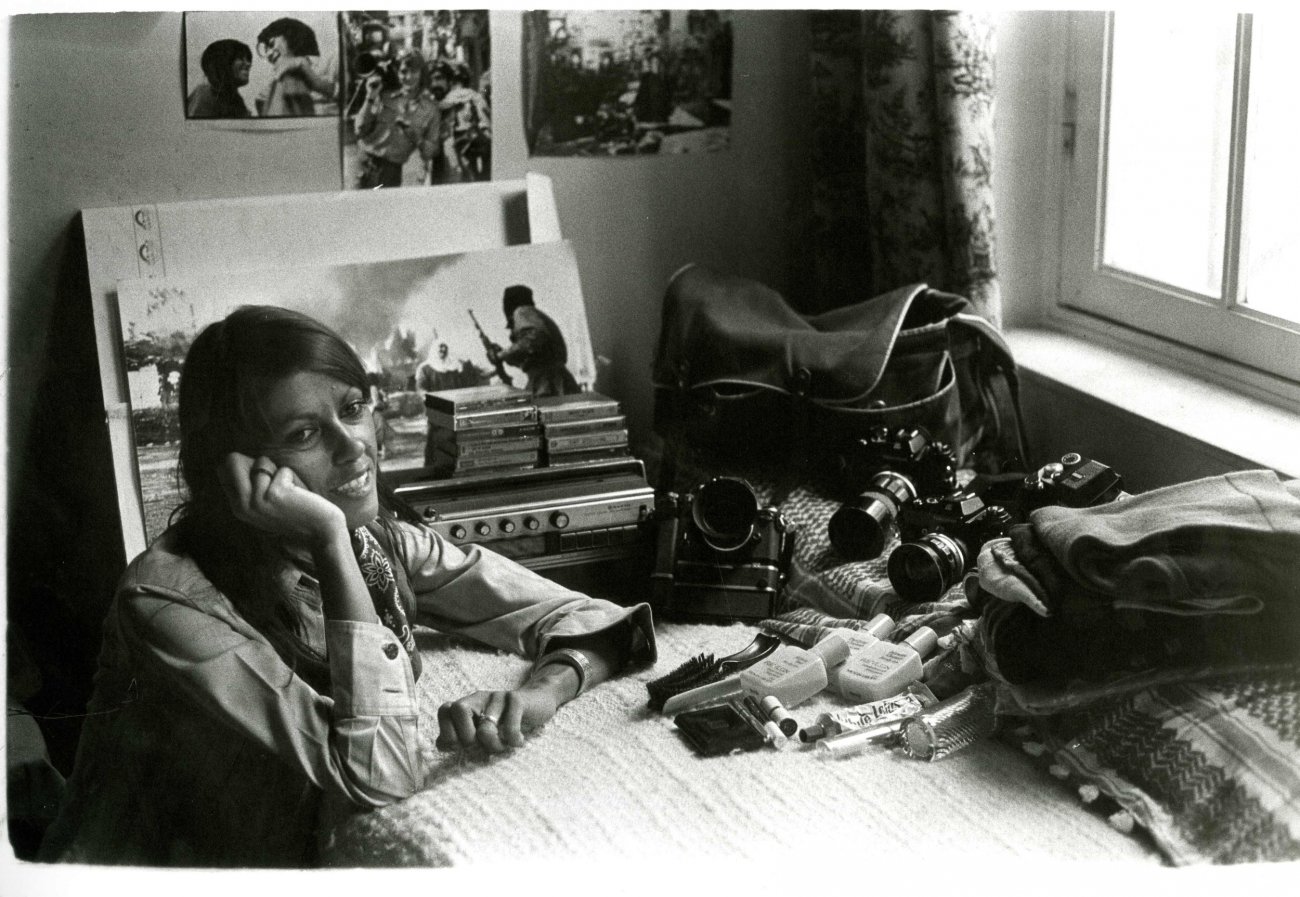

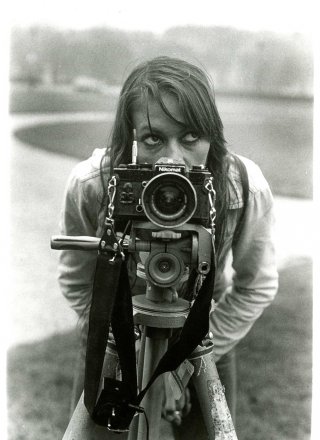

Françoise went through wars, like Moses through the Red Sea. Soldiers would hang a Do not disturb sign at the entrance to battlefields where slaughter was not for public viewing, and while Françoise would pretend to take notice, then, with her camera hidden in her curls, in a couple of clicks, she would have the shots in her bag, recording part of the history of the world. The shutter would not go off like machine-gun fire determined not to miss anything; her eye would light on what she knew was essential, in that split second; there would be one click and then a smile. She was from a different realm, had the elegance of a ballerina, and passed virtually unnoticed, nothing more than a little bird landing on a branch. Her pictures were not stolen, and were never staged – nothing but the raw truth. Her job was complicated, but she did it simply, lending her eyes for others around the world to see, showing them that war is never nice. Here was a woman in a man’s world, a woman who remained a true princess. She cannot be incongruously labeled a “war photographer,” as if such a photographer had a predilection for bloodbaths. Fifi, as she was known, was afraid of nothing and was always prepared to die, yet detested the most ordinary forms of violence. She covered wars the way mountain climbers conquer mountains, because they are there. Back at the hotel, chatting in the bar at the end of the day, she preferred to talk about her cats and how she loved them, rather than go over the ambushes and bombings.

Preview

In Beirut, as a photographer for Time Magazine, she lived in an apartment on the coast, exposed to planes maneuvering and canons facing in her direction. Whenever the fighting reached dangerous levels, Fifi would phone me at the Hotel Commodore (Noah’s ark for journalists) and would say, “Things are getting pretty hot at my place. Can you come over and help me move out?” We would be like the two characters in the film Wings of desire, meeting up and walking along the streets, past ruins and explosions, carrying her two Siamese cats in one cage, and her little red birds in another.

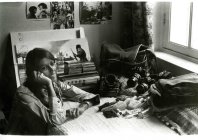

She was a very attractive woman and worked as a model at one stage, before falling in love with the photographer Yves Billy. That was in the days of flower power, impulsiveness and total freedom, hippie-style. Fifi went to Vietnam with Billy, and from that point on her life was no longer her own. After that, all she did was “see.” In Saigon, she was stealthy, keeping clear of the mob. She was the only one there to photograph the Viet Cong tanks entering the city of Saigon. In Cambodia there was more suffering waiting for her; she sponsored a child there. History moves in its own way, setting its own time, and war soon reached Lebanon, where Fifi was to spend almost ten years, in the midst of crime and mass graves. In 1977, she was the first woman to be awarded the ultimate accolade in photography, the World Press Photo for one of her shots of the Karantina massacre of Palestinians. The scene is so powerful, yet so simple that the Gamma editor selecting shots for the agency to offer the press did not put it on the list. A few days later, once Fifi had retrieved it from the “rejects,” the picture became an icon.

The end was appalling. Cancer plus a medical error left her in a wheelchair, with years of pain, in and out of hospital, but never without a laugh. In the early hours of September 3, 2008, before the light, the very lifeblood of a photographer, had filled the sky, her heart, the strongest part of her, surrendered.

Jacques-Marie Bourget