Riots in Turkey

Angelos Tzortzinis

Nobody could have imagined that in the last days of May 2013, an environmental protest by fifty people opposed to the plan to rebuild the historic Taksim Military Barracks on the site of Taksim Gezi Park would spark a massive reaction from the Turkish people.

But this time the demands were not just about a park and trees. The protests went beyond the Gezi Park development to become broader anti-government demonstrations.

As Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan drew more and more criticism, accused of becoming increasingly autocratic, the Turkish people had an opportunity to express their concerns on freedom of the press, freedom of expression, freedom of assembly, and government encroachment on Turkey’s secular state.

Prime Minister Erdogan referred to the protesters as ‘‘çapulcu’’ (looters), and the people responded saying that they were simply claiming their rights.

Preview

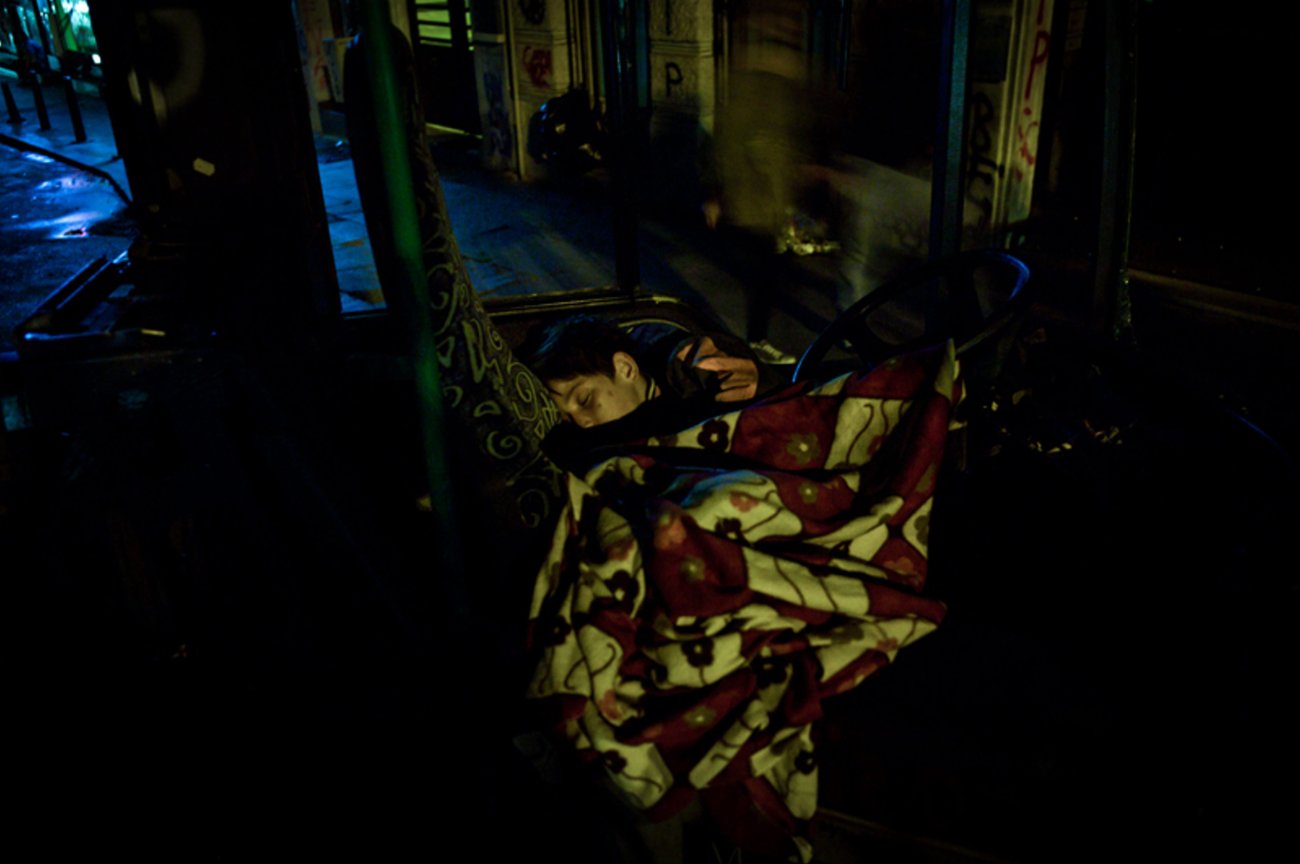

Tens of thousands of protesters from across the political spectrum gathered in Taksim Square and other cities, speaking up and speaking out, calling for a better Turkey.

The government’s response was swift and violent. Police moved onto the square, making excessive use of teargas, rubber bullets, pepper spray and water cannon, leaving hundreds of demonstrators injured.

When the police finally cleared Gezi Park after weeks of demonstrations, silent protesters appeared: a new form of protest – the Standing Man or Standing Woman – was initiated by a lone protester, standing immobile in Taksim Square for hours, staring at a portrait of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the founder of the Republic of Turkey, and the Turkish flags on the Ataturk Cultural Center, a vision of hope for change.

Angelos Tzortzinis