Diamond matters

Michael Yamashita

National Geographic Magazine

Diamond is carbon, crystallized under pressure over millions of years. The crystals rise to the surface during volcanic eruptions. Some fall back into the volcanic pipe to form blueground, called kimberlite. Some is spread across a large area through erosion and flood and can be found in river beds or just under the surface. In the 1990s I did a number of photo-reportages during the fighting in Zaire (present-day Democratic Republic of Congo), Sierra Leone and Angola, conflicts which were often dismissed as tribal wars, the final convulsions of the Cold War. By degrees, however, they increasingly became conflicts over raw materials. The diamond deposits were, for the most part, controlled by the Angolan and Sierra Leonean rebels, who used the gems as a means to buy weapons. Governments got in on the act too and the terms “blood diamond” and “conflict diamond” were coined. At the time I did a number of reportages on the subject, without, however, being able to picture the whole industry; both rebels and dealers were very suspicious.

Preview

Meanwhile, villagers, given special land allotments and spared military service, attempt to conduct normal lives inside the security zone. A half-dozen armed soldiers guard a farmer as he rides a tractor through a field to harvest crops. Busloads of tourists are unloaded inside the Joint Security Area to gape at soldiers, shudder at all the land mine warning signs, snap a picture of the unsmiling North Korean guards, and buy a souvenir strand of barbed wire. And in fall endangered cranes on their migration route fly into DMZ to feed in the stubbly fields. A half-century of stalemate has created one of the largest patches of surviving wilderness in South Korea.

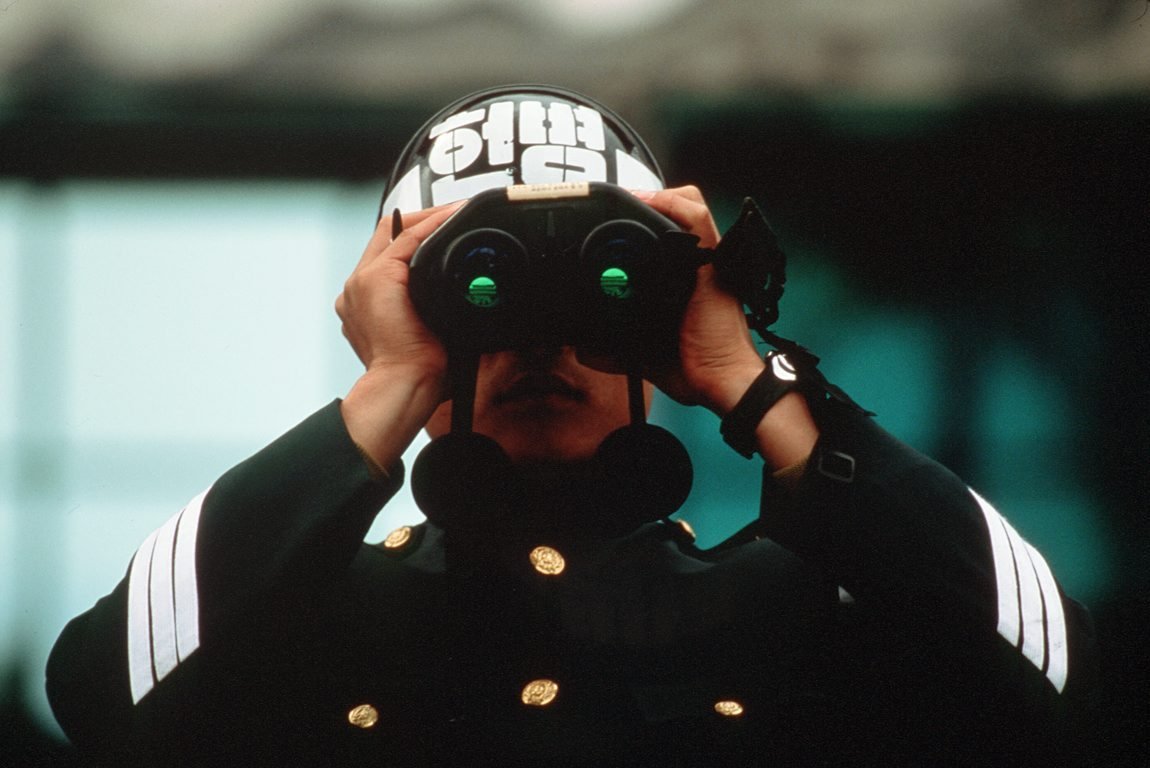

Contrasts are part of everyday life. U.S. troops live at bases equipped with playing fields, computer rooms, fast food stands, and even golf courses. The South Korean conscripts hunker down in unadorned camps where they practice martial arts and endlessly go on patrols. The North Koreans, observed by thousands of eyes through binoculars and video cameras, man guard towers lucky to have heat and light on many nights. There are guard towers on beaches, on mountaintops, along busy highways, and in fields.

Meanwhile, just 35 miles away in Seoul, few of its 11 million densely packed residents, dwell on the fact that hundreds of artillery pieces are armed at them, or realizes that at any moment tanks are rumbling through little farm towns on maneuvers, or that the North Korea leader Kim Jong Il has threatened to turn Seoul into a “lake of fire” if provoked. The DMZ seems like a thousand miles away.

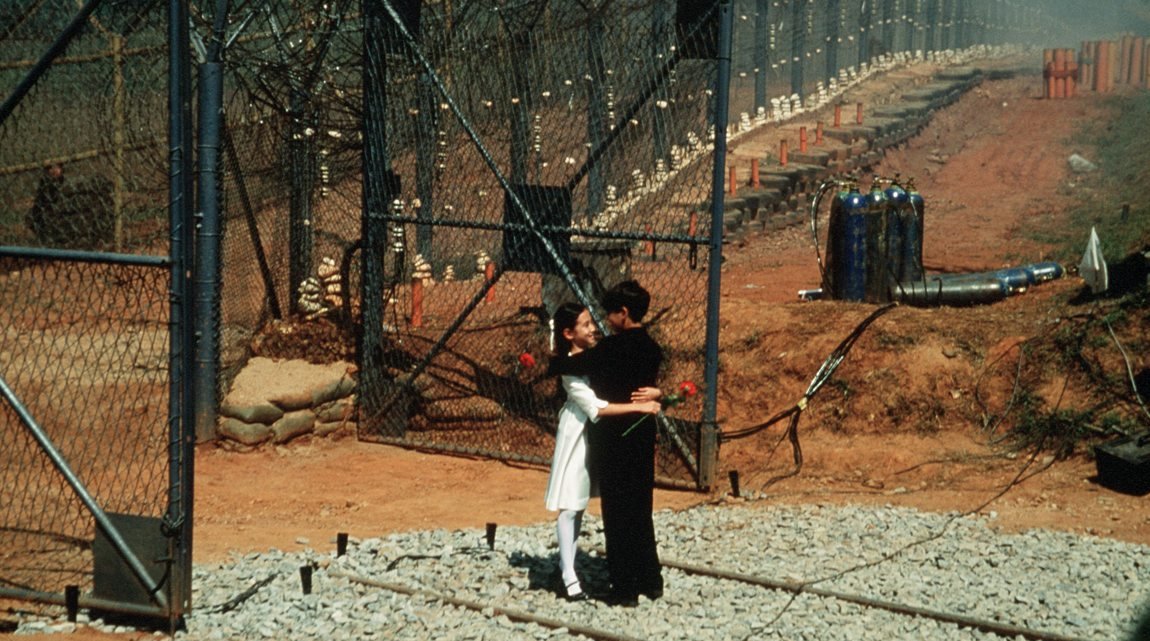

For three months, armed with cameras, I traveled the length of the Demilitarized Zone, dealing with severe terrain, freezing mountaintop temperatures, paranoid officers, armed guards, deafening target practices, close-quarters live-ammo drills, violent protest rallies outside U.S. military bases, heartbroken South Koreans wishing they could see family members in the north again, and symbolic handshakes across the border. I spent a week inside North Korea at a mountain resort. Every day felt different because every day soldiers were preparing for a war that could start at any minute.