The Last Empire - 20 Years Later

Sergey Maximishin

Focus

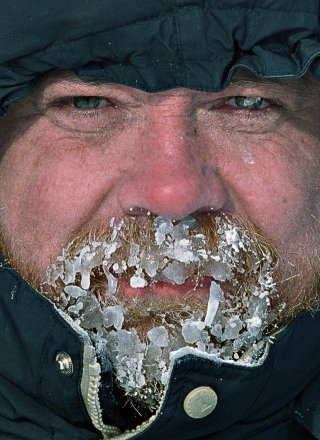

The goal is ambitious: a collection of passionate, visual comments that bravely narrates the ineffable: bits of everyday life in the former USSR, whose territory spreads over eleven time zones. Since the Gorbachev period, the West has tried to be reassured about the Eastern European giant, alternating sympathy and optimism with a variety of sudden attitude changes. The fact, however, remains: twenty years after Perestroika, for those who live on my side of the Iron Curtain, what happens in the former empire of the Communist Czars is still a mystery. A true artist, Sergey Maximishin relies on the language of his images – elegant, convincing, recognizable, and always clear. He does not want to soothe our anxieties, he does not want to give us answers. From Moscow to Kamchatka, from St. Petersburg to Chechnya, Russia has a lot of enemies: poverty, disease, greed, riches obtained unjustly and outrageously. He has no time to praise beloved heroes. The favorite protagonists of his wordless tales are often nameless. Specific times, specific places. Sergey catches the essence of each and every character. Masterfully, switching his narrative tones, mixing drama and irony, he does not resort to cynicism or useless flattery.

Preview

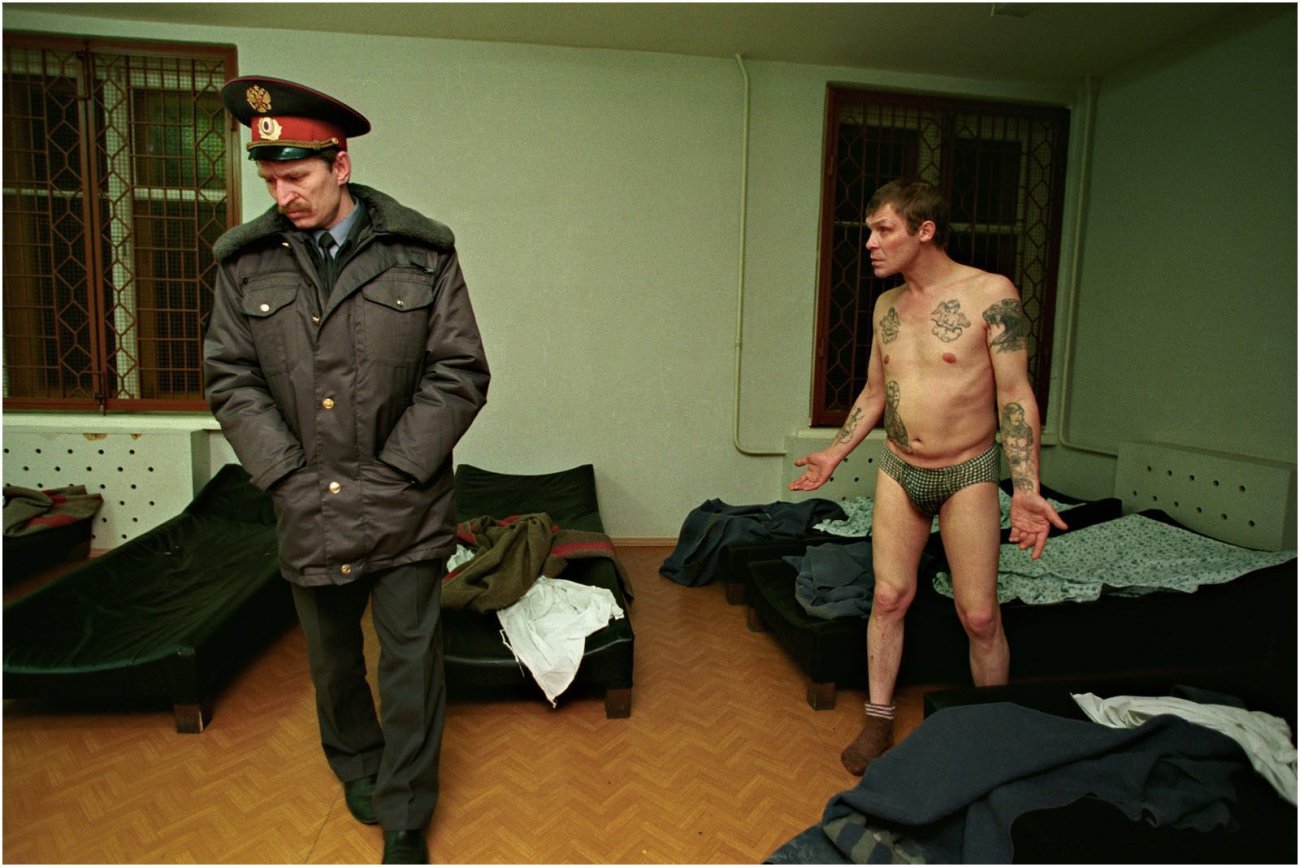

Maximishin avoids the spotlight, both when he hides behind his camera during a shoot and during the World Press award ceremonies, succumbing to his natural inclination to modesty and discretion: he observes and captures the moment. His down-to-earth attitude helps him create priceless images for generations to come. His sincere empathy with his characters makes us enjoy even the harshest subject matters; prisons and mayhem in the background make us think, they do not repel us. Sergey gracefully, tastefully, unconsciously interprets the reference points of the West, dismantles them and offers new readings which in turn are shaded, controversial or modern: nowadays one can reach Bulgakov’s Vorobievy Hill by chair-lift dressed like a businessman; modern-day Raskolnikovs get Nazi symbols tattooed on their arms; Zov Ilycha (Lenin’s Call) is nothing but a restaurant with waitresses in cinch-waisted belts; Anna Karenina’s lover, Count Vronsky is now a nouveau riche surrounded by women in mini-skirts. Ultimately, having paged through the book for the first, the second and the third time, the most indelible impression is the sweetness and the depth of Maximishin’s eye which settles on almost all the characters in his photographs: the rich colors and naturally tasteful composition restore power and integrity to a child from Grozny trying to attract the attention of a kitten, to fishermen from Kazakhstan, prisoners from St. Petersburg and employees at the Mariinsky Theatre and the Hermitage Museum who keep a fairy tale alive for a few rubles. Maximishin’s images remind us that the former empire houses everything and everyone in its post-Perestroika era: real people trying to trudge along and fake czars; the rush to be modern and the emotional attachment to the past; sincere love for their land and nationalism at its worst; and that today, as before, devilish Voland lies in ambush.

Chiara Mariani