The Marsh Arabs of Iraq

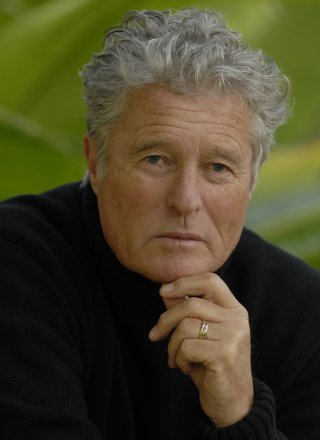

Nik Wheeler

In Southern Iraq, the muddy waters of the Tigris River merge with the blue waters of the Euphrates to form a mighty flood plain of reeds and water - the marshlands of ancient Mesopotamia. Often considered the site of the legendary Garden of Eden, the Marshes and their surrounding desert cities have been inhabited since ancient Sumerian times. Sumerian seals and tablets in the British Museum show a way of life that flourished until the late 1970s and still partially exists today.

Within this waterworld of lakes and giant reedbeds dwelt a community of Marsh Arabs - the Mada’an. Unlike their desert counterparts who lived in tents and rode camels, these tribal Marshmen built villages of houses, some as large as small churches, made from woven reeds standing on small islands. They paddled canoes with high prows, fished for carp with pronged spears, raised water buffalo grazing among the reedbeds, and cultivated rice on the muddy banks. The women gathered reeds to weave mats for roofing and floor coverings, and to sell at nearby markets. In the 1950s, more than 100 000 people lived in the wetlands, an expanse of 20 000 square kilometers.

Preview

Throughout Iraqi history, this remote area has been a refuge for criminals, draft-dodgers and political opponents of the Baghdad government.

In the late 1970s, I spent several weeks inside this closed community, firstly on assignment for National Geographic, and later working on a book devoted to the Marsh Arab way of life. The normally paranoid Iraqi government, often wary of showing the “primitive” aspect of the country, granted me exceptional authorization for access plus logistical support, even providing a military helicopter for aerial photos. The Iraqi government was interested in my report as a record for posterity showing the details of this historic civilization before they began systematically destroying it. Saddam Hussein was determined to bring the marshes under government control. Committing one of the great ecological crimes of the 20th century, he built a network of sluices, embankments and canals to divert the flow of the rivers and drain the marshes of their lifeblood.

Disaster first struck the Marsh Arabs after the Iran-Iraq war, largely fought around the wetlands along the Iranian border, when Saddam used gas on several villages, which, in his opinion, had not fought bravely enough. Then, after the First Gulf War when the Shiites of the South revolted against Saddam’s regime anticipating US assistance which never came, the Iraqi president sent troops to bomb villages and terrorize the population. The inhabitants fled, and by the year 2000, 90% of the wetlands had been destroyed and the people displaced. After the US invasion, the dykes and sluices were reopened and parts of the marshes were reflooded. International aid agencies have helped a small percentage of Marshmen resettle in their villages and resume their traditional way of life. Progress has been slow with several years of drought, but many birds and fish, and a few Ma’daan have returned to the wetlands.

Nik Wheeler