Login or register for free to continue browsing

Access all this year’s exclusive online content

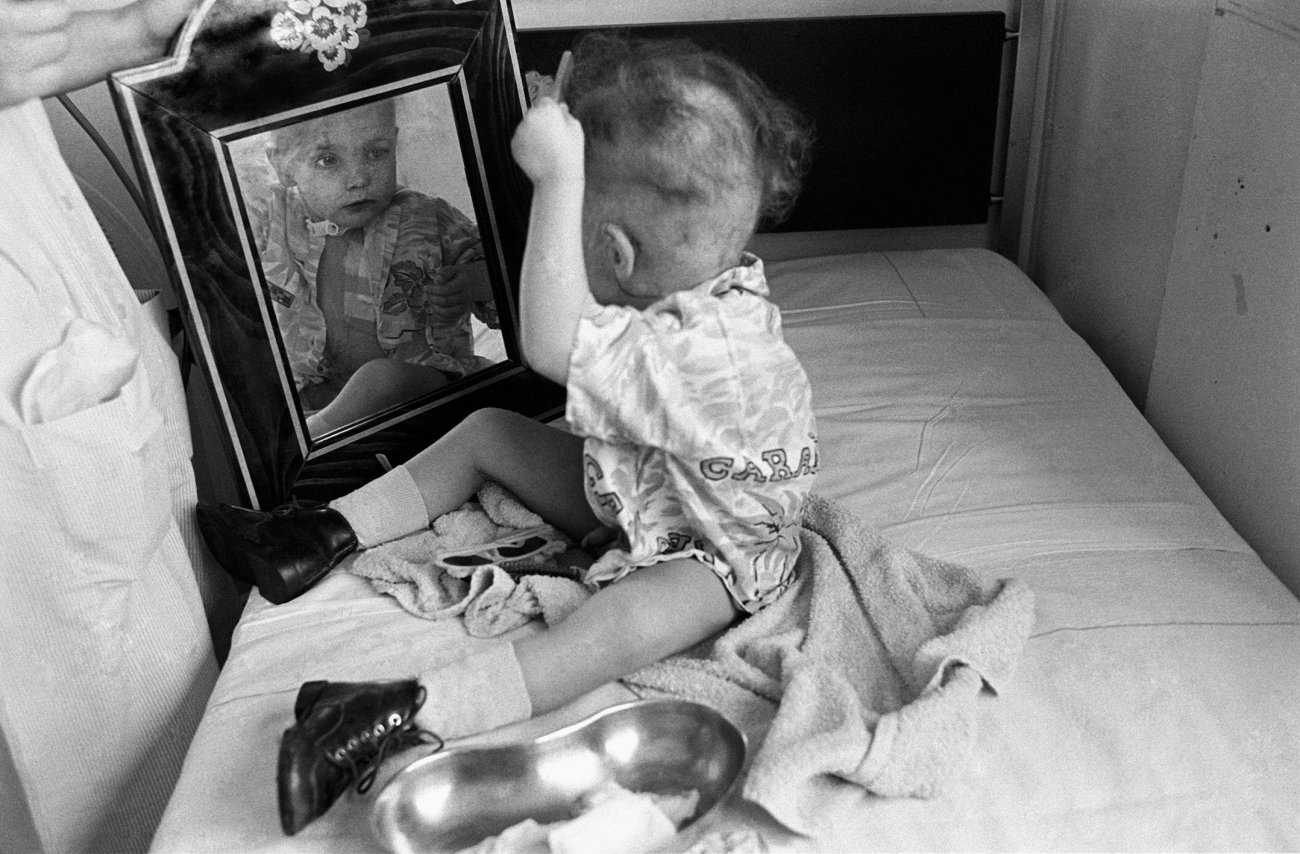

40 years of social photography

Jean-Louis Courtinat

For almost forty years, Jean-Louis Courtinat has been driven by the challenge of photographing sensitive subjects with sensitivity. Here, the adjective “sensitive”, which describes the subjects of his reports, takes second place to the noun “sensitivity”, which describes the way he looks at people who have been damaged by illness, poverty and homelessness. His approach is refined without being affected, compassionate without being sentimental, intimate without being voyeuristic. His photographs do not show men, women and children who are frail or weak, but rather who are restored in their dignity as human beings. They give them substance, bearing witness to everything they have been through.

Almost thirty years separate “Les damnés de Nanterre” and his investigation, “Des êtres sans importance,” part of which was produced in connection with the major commission “Radioscopie de la France.” In both of these collections, which are archived at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, we can see the same quality of relationship between the photographer and each of the protagonists in his photographs: the quality of their presence is a result of the time he has taken to understand them.

Preview